The Country Wide Podcast: Are biodiversity credits the golden ticket to more native trees vs pine trees?

- CarbonCrop Team

- Mar 26, 2024

- 15 min read

CarbonCrop co-founder, Nick Butcher, joins Sarah Perriam-Lampp for a discussion around CarbonCrop, forest carbon removals, and questions how would you go about to calculate a credit on the living ecosystem nuance of ‘biodiversity’ into a unit that can be traded for monetary value. Listen to the episode or read the transcript below.

Interview starts at 27:20

CarbonCrop Interview Transcript - The Country Wide Podcast

Sarah

Now, I wanted to jump in and talk to the Carbon Crop team with regards to the whole technology that's been developed rapidly in the last couple of years. Where landowners are able to capture value around the carbon market but at the same time, how easily is this to be applied across into a biodiversity credit, so to speak, like Carbon Z announced last year. I've got the CTO acting CEO, as well as co-founder, Nick Butcher with me on the interview. This podcast. Nick, thank you for your time. For those who haven't heard of CarbonCrop, could you please give us a little 101 on how the technology works to, as we said, capture value from carbon sequestration.

Nick

Yeah. Happy to. Thanks for having me on Sarah. So, the basic idea that we had when we started the company was to help people access incentive markets, specifically carbon incentive markets, to support the restoration and protection of forest. That sounds like kind of a mouthful, basically restoring forest costs money.

That's true whether you're acting in a timber market or a carbon market or a biodiversity market. And if the market exists, but you can't access it, then you don't get the money, which means that you can't restore the forest. What we identified early on in the product research was that even where the markets do exist, they can be quite hard for the average landholder to access.

And that meant that the incentives weren't flowing and the forest wasn't getting restored or wasn't getting restored as well as it could. Um, so we've built a technology platform and sort of services solution that helps people restoring forests, get the activities recognized within existing market frameworks so that they can get paid, which creates a better experience.

Incentive effect, which encourages them to, well, both encourages them and enables them to restore new shares.

Sarah

So, of course, we're not going to probably get into the personal viewpoints around carbon markets and ETS. But at the same time, there has been an ETS review from the Climate Change Commission.

How active have you been involved in that discussion and where do you think it's going to lie, what 2024's got with the new government?

Nick

We've been quite active in it from a number of perspectives, there's probably certain podcasts on its own to catalogue all of my opinions. At a high level, we think that forest is important, biodiverse forest is important, New Zealand is achieving its climate change mitigation and emissions reduction targets.

And I generally think in terms of especially net emissions, I think that's almost more important than gross emissions because, you know, if we had a magic machine that could suck all of the carbon out of the atmosphere and turn it into diamonds and store it in a tidy pile. It would be mad not to turn it on and to say no, we're worried about gross emissions.

Like the atmosphere cares about net emissions. That said, it's easy to look at some of the policy responses and see the risk of perverse incentives. Like we don't want to see the whole country just in pine monocultures. We do really want to see biodiverse forest restoration and permanent forest restoration.

That's sort of got high environmental co-benefits. I think some of the policy that the new government was indicating in the lead up to the election around this with restrictions on exotic afforestation on farmland on the sort of the more productive farmland is a good idea. I'd be happy to see that progress.

It could be that we get to the stage that we're looking at establishing further forest on quite high productivity agricultural land. Like it's hard to know what the agriculture sector is going to look like in 30 years with sort of cellular meats and sort of artificial fermentation and this kind of thing, but I definitely don't think we should start with a high productivity agricultural land. Like there's a huge amount of marginal farmland that's unstable and erosion prone in New Zealand. If you're going to allow something to regenerate, start with that and set your policy incentives accordingly.

Sarah

I'm looking at some carbon market commentary and you know the ultimate goal is, and everybody loves, New Zealand native forests therefore we want to plant them. However, I mean, it's considerably costly. Cost difference around per hectare rates for planting that verse.

So, how does the carbon market stack up any differently if the sequestration rates are so much slower and more expensive to establish for natives on farm? So, is biodiversity the next benefit for our sheep and beef farmers and how would that even work?

Nick

Yeah, it's a really interesting point because people do have a very different emotional response to blanket, single age class, monoculture, genetic clone pines, versus biodiverse native forest, and it's not the carbon.

Like for, for all the criticism people like to heap on pine forest, it's really good at capturing carbon and it's actually quite good at doing it durably. And another really important thing that's actually missed is that often people say “oh well, it won't necessarily last.”

Even if we only have the forest there for 30 years, it's still kept the carbon out of the atmosphere for 30 years and that's incredibly important because, like everybody talked about, bending the curve with COVID? Like, if you just stop people getting infected for six months, that's still a really good thing, even if they get sick later. Same with carbon.

If we temporarily draw down carbon, it's still extremely valuable, but people do perceive there as being a big difference. It's the same carbon molecule tied up in the wood. Which means that whatever it is, it probably is something like biodiversity. So there's all these ideas, like, does a pine forest have less positive biodiversity value than a native forest?

Does it have a negative biodiversity value? Could you use, sort of, relative biodiversity value as the compensating mechanism that makes it cost effective even from an opportunity cost perspective to put in native forest instead of exotic forest. This is definitely going to cost you more money to establish under most methodologies as you there's an argument to be made that if you just allow for natural regeneration the cost of establishment of natives could be quite low but in many environments, you could be waiting a hundred years and even then, the carbon yield is going to be enormously lower. I don't think that there's any real debate about that within the sector. There's sort of various papers going around saying that the natives have been a bit short changed, depending on the environment, and with some methodologies, the yields could be significantly higher than the look up tables, but I've never seen anybody suggest that they'd get any lower. Close to the sequestration rates you get from eucalyptus, redwoods, radiata or similar.

Sarah

So there's a big gap that you have to make up. Natives are, in many cases, what we would like to see restored on these marginal, erosion prone hillsides, so it's kind of a question of how you get there as well. Because the opportunity cost doesn't land in your bank account, so to speak, in indirect benefits, and I could list them as long as my arm as well but at the same time, the concept of a biodiversity credit could potentially be that dollar landing in your bank, as well as those indirect benefits. Could it not?

Nick

Yeah, but potentially. And I think that gets you close too. Let's say that we don't change the carbon market and the access to carbon markets for exotic and native forest remains as it is today. Assuming that you've got some, just a simple economic actor, who's trying to make the most money that they can for their farm.

And a lot of farmers have a lot of debt and are under a lot of financial pressure, so it's fair enough that they follow the money. The amount that you're going to have to pay them for a biodiversity credit to put in natives rather than exotics is going to be the difference in the establishment cost and yield.

And that's a pretty big number. There was some great work done, I think, in the Last Billion Trees Program around targeted incentives for natives, where the sort of upfront cash incentive payments were a lot higher radiata, but especially at the current price, it still wasn't enough. I think that I like the idea in principle, especially for the areas where we want to see long term permanent forest.

I think at least the end state goal should be biodiverse native forest. There's a lot of discussion around potentially having transitional forestry approaches and those may work depending on the environment, but if you're just trying to go direct to native forest through planting a biodiversity payment that essentially recognizes the additional value of native forest could be a way to do it, but it would have to be a pretty large number like 15, to throw a figure out there, is not going to be 500 or 1, 000 or 2, 000 because the costs are still just so skewed and the returns are so skewed.

Sarah

How closely do you keep an eye on the International Banking Alliance and Green Finance to incentivize offsetting by some of these big corporates and their offsetting choices, so therefore the value changes?

Nick

I wouldn't say an especially close eye. We're sort of an enabler for the markets as they develop.

We're certainly keeping an eye on it and trying to stay abreast of it, but there's a lot to keep up with. As a summary though, I would say that we are generally strong advocates of compliance carbon markets. I don't think that we're going to get there with voluntary action. And like, there are different forms of compliance.

The ETS (Emissions Trading Scheme) is one of them, sort of really strong social licence expectations internationally can almost become a form of compliance, even though they're not actually the law. Like it's just, it's not the cost of money though. You're going to be alienated if you're not doing this thing. It's an interesting figure that I often think back to is that the New Zealand ETS carbon market is almost as big as the global voluntary carbon market.

Those are the relative scales. I think the global compliance carbon market, which is dominated by the EU, is something on the order of 50 to a hundred times as big as the, sorry, global compliance market's roughly a hundred times as big as the voluntary market. I just don't think that people are voluntarily going to start spending hundreds of billions of dollars that it will probably take to source removals.

I'm impressed that people are spending a couple of billion, spending hundreds of billions seems like it's going to take regulation, and that regulation already exists in New Zealand and the EU, and in other places, and I think that will be what powers the incentive markets that really drive massive national and international scale action.

So with the banking stuff you mentioned, I'm not sure where that sits on those spectrums because there's still a little bit of a disconnect between the international voluntary carbon frameworks and the national and international frameworks that exist under the Paris Agreement kind of mechanisms and I think there's sort of a reconciliation happening there at the moment and how that pans out will have a big impact on future carbon markets and potentially on future biodiversity markets, although that might be more the Montreal agreements rather than the Paris ones.

Sarha

Yeah, I mean, that's the thing is our banks around the world are trying to decarbonize their books. It's going to have a direct effect for our farmers, um, in terms of cost of money and it is, but at the same time, in terms of driving the value of that interesting take out there around Voluntary biodiversity credits. Also how, through the likes of your technology, would you even be able to monitor biodiversity versus carbon?

Nick

It leads directly to a very good question, which is: what is ‘a biodiversity’ and how many of them are there in a tree? And how many of them are there in a kakapo and how many of them are there in a dolphin?

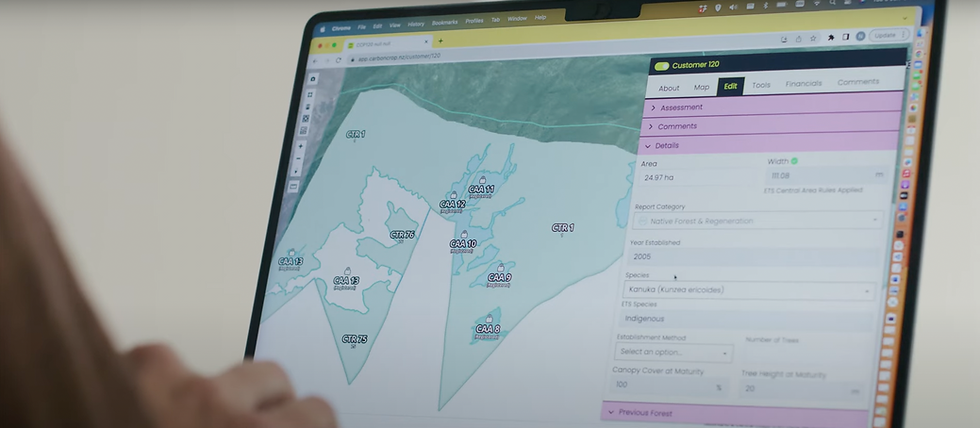

Which is why we've been, we're quite careful not to quantify biodiversity. We count biodiversity related metrics. Like our technology can monitor the area of indigenous versus exotic forest on a property versus pasture and similar, and the biomass associated with the exotic forest because that's linked to what we recognize with carbon removal units.

Sometimes that's very useful. There's a premium in certain markets and especially in the primary sector in New Zealand when people are looking to create a net zero product. So for example, a primary product where the emissions associated with that product are balanced out by the carbon removals associated with that product.

They're really keen to have the carbon removals. So that's the carbon that's being pulled down into vegetation, being pulled down into native vegetation just because the brand story that goes with it is so much stronger. So there kind of is a premium there in the carbon price already for biodiversity because people don't necessarily want to pay the same price for the exotics.

But that's the kind of stuff we do. So we'll say these are carbon removal units which were quantified, we've made them traceable, auditable, they're consistent with standards, and they have co benefits of sort of habitat for biodiverse native fauna or, and you could quantify that in terms of a number of hectares or a fraction of coverage within a farmer state.

To kind of go from that to comparisons across areas of biodiversity, like the value of 10 hectares of alpine grassland versus 27 native skinks. I just don't know how you do it, really. I think it's quite important, and we almost do this in general at the moment because there's a lot of grant programs for species protection and habitat restoration and stuff. Everybody's constantly having to decide, we've only got 10 million dollars, what are we going to use it for?

I think just reducing it to a simple universal credit was like a sustainability unit. There's kind of a lot of complexity hidden under the hood there, which is kind of unacknowledged, and it often ends up just looking closer to biodiversity grants to me, looking more like grants or sponsorship for activities rather than something that's kind of directly comparable in the way that.

A really good example would be: there's already so much argument within the emissions monitoring sector over the comparison between a ton of CO2 and a ton of methane. And there's this generally accepted internationally standardised GWP 100 warming factor of 36 or something like that, that you can prove in a laboratory. To quite a high level of competence. Yet it's still argued about endlessly.

To get to the point that you could compare even just the value of grassland with the value of forest, because grassland isn't barren, a biodiverse regenerative pasture is actually a really productive environment. Is it worth more or less than forest?

I don't wanna be the one answering that question, but if you ask me how much carbon was in one of the other of them, and how much that helps mitigate climate change, it's easier to provide an answer.

Sarah

I think that's a big appeal, I'm assuming that our audience of sheep and beef farmers across New Zealand, considering is the fact that it's like carbon madness and isolation by itself being the only thing that our brands are seeming to be talking to us about, as well as our processes that the debate around methane and ruminant animals is because of the interconnected biological living systems that we work in farming sheep and beef, which is very different and extensive, to hill country. And so when you've got the likes of an AllBirds chasing net zero, but you have a merino operating in quite a biodiverse environment, that's not taken into account.

It's just the sequestration of something. Isolated. And I suppose that's where the attraction lies, but it's so great to talk to you, Nick, about the complexity of even acknowledging that a credit is possible.

Nick

Yeah, I think the NZ Merino one with AllBirds, there's some public aspects of the program we can talk about.

I would actually say that AllBirds were a great example that they do actually. Put a value on the co-benefits and the biodiversity. I don't think that that program would have had the same appeal to them if it had just been a massive new forestry block. It was that it was like mosaic land use and sort of integrated land management that was complementary to farming and that they were really keen on that, which is great, obviously.

On the sheep and beef farmers, I think that's where biodiversity is actually extremely important, but also as sort of a broader perspective on sort of ongoing carbon removal delivery is very important because there's a huge amount of unrecognised benefits that are coming from the activities that sheep and beef farmers are already taking, and if you just have this attitude of how big's your forestry block and did you plant it after 1990, it's kind of disregarded and they're really short changed.

So we've been very strong advocates of if somebody's doing good stuff, then make sure that you're considering that on their balance sheet at the same time as you're talking about how to impose a levy for the methane they're emitting. Otherwise, it's just totally unfair. Especially if you get to the point that you say all you guys have protected and restored your health sides, from generation to generation. That doesn't count for anything. We're not going to recognise it. I'm only going to give you brownie points for the things that you've done since last year.

It's like, well, great way to incentivize late action. You're just going to make everybody wait until the last possible moment, which is not what we want. We really want earlier actors who are enthusiastic and who take the initiative and drive things forward.

For that to happen, you have to recognise it. Otherwise it's just a bit of a disaster.

Sarah

Well, and the classic case in point is a 20 hectare Marlborough Sounds property that my mum has of beautiful old stands of bush that she won't get anything for, but by nurturing it, leaving it as it is, the biodiversity is incredibly rich.

So yeah, it's, it's a very interesting thing. Last parting question is, what's your fear of James Shaw stepping out of politics and what will that mean? Because I do know that there's been a few sheep and beef farmers that have either loved him or hated him in that role, but everybody very much respects the role he has played in the practice. Pragmatic-ness of the discussion and Rod Cast stepping down his chair as well. What do you think the dynamic's gonna look like?

Nick

I think you almost summarised my thoughts and the accolades that you heaped on James. Like, I think he is fantastic and a huge loss to politics in New Zealand that he is stepping down.

I've admired his pragmatism. Yes, people can be pragmatic and uninformed. He's both pragmatic and informed, which is like a super rare combination. I think there's other people there who are looking to pick up the flag and not just on the green side.

There's a lot of pragmatic, environmentally sensitive people across the political spectrum, and I think that, my hope is, almost that the cross party collaborations between those pragmatic, forward looking groups hold sway over the sort of borderline extremists on both sides. Because there's extremists on both sides, people who say we should basically scrap New Zealand farming and restore everything into its pristine natural state. That is not a good idea. Neither is it a good idea, in my view, to like mine, mine, mine, drill, drill, drill, destroy the natural habitat. The answer is somewhere in the centre, and I think providing the tools for landowners to be successful in that space and not be constantly bounced back and forth is what we really need to see from the next generation of politicians.

But I'll be sad to see James and Rod go.

Sarah

Whilst we're on that, can I also say that the announcement this week, podcast going out the following, around the scrapping of significant natural areas, SNAs, Andrew Hoggard himself has been right across the spectrum of being informed as well of understanding the balancing act between letting sheep and beef farmers actually do naturally what they already would do in terms of protecting natural areas versus the ludicrously of putting a line around it.

Your thoughts on that announcement as well, just while I've got you, Nick?

Nick

I'm not actually across the announcement, and I might get myself into trouble with my opinions on SNAs, which I have to admit I'm not an expert in. But I think that that was an example of a very perverse penalty applied to those who had done good early, and I didn't like it.

I think that it is a role for an incentive market. If you want people to protect and restore an area of their farm. Enable them to do so, and encourage them to do so, and let them make the decision and be a good steward of the land. Don't hit them with a stick. Especially don't hit them with a stick because they did a good thing in the past.

That's just going to lead to an obvious outcome of people being, and we know of cases where people proactively cleared biodiverse habitat because they were, scared of the implications of the SNA. And that's a horrible outcome. They didn't even want to do it, but that's what you should expect when you come up with these draconian measures that basically box people into a corner.

So, yeah. In a nutshell, I don't think it was particularly well conceived or implemented, and I'm not that sorry to see it go, but I think that some of the intent of it was good and could be achieved with well designed incentive markets.

It's all about the incentive. I wonder who I've made mad now.

Sarah

All about the incentive.

Nick

The great thing though is that people are already incentivised like almost all of the farmers we talk to like they are super motivated to be good stewards of their land and they have taken multi generational perspective on it, so it's not like you have to persuade them not to be destructive that's their natural inclination is to be restorative.

You just have to help not get in their way. That's my view.

Sarah

Love it. Thank you so much for your time, Nick.

Comments